The History of American Football: Evolution, Key Moments, and Legendary Players

History of American Football

American football is a version of soccer that evolved from English rugby and soccer (association football); It differs from football specifically in allowing players to touch, throw, and hold the ball in their hands, and from rugby in allowing each side to exchange possessions. This game played with 11 players, originated in North America, primarily in the United States, where it eventually became the largest spectator sport in the country. It also developed simultaneously in Canada, where it evolved into a 12-a-side sport, although Canadian football never achieved the great popularity and status of ice hockey there. In the rest of the world, American football has not received as much attention as other American sports such as basketball and baseball. However, since the 1980s, teams and leagues have been established in Europe, primarily through the marketing efforts of the National Football League, and the sport has gained international popularity through television. The game is sometimes called net soccer because the vertical yard lines define the rectangular field.

Football in the United States

The game appears.

History of American Football

Gridiron football was the creation of America’s college elite, a fact that shaped its distinctive role in American culture and life. After decades of informal student-organized sports permitted by the faculty as an alternative to more destructive hazing, the first intercollegiate football game was played on November 6, 1869, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, between in-state rivals Princeton and Rutgers under Football Association rules derived from London. This football-like game became dominant when Columbia, Cornell, Yale, and a few other colleges in the Northeast began playing the game in the early 1870s, and in 1873 representatives from Princeton, Yale, and Rutgers met in New York City to establish the Intercollegiate Football Association and adopt a common law. Conspicuously missing was Harvard University, the country’s largest university, whose team insisted on playing the so-called “Boston Game”, a cross between football and rugby.

In May 1874, in the second of a two-game set with McGill University in Montreal (the first was played under Boston game rules), the Harvard players were introduced to the game of rugby and immediately preferred it to their own game. The following year, in the first football game between Harvard and Yale, representatives of the two schools agreed to “soft rules” that were essentially Harvard’s rules. When spectators (including Princeton students) as well as Yale players saw the advantages of the rugby style, in 1876 the stage was set for a meeting of representatives from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia to form a new intercollegiate football league based on rugby principles.

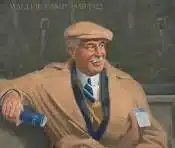

Walter Kemp and the Creation of American Football

History of American Football. Rejecting the traditional method of putting the ball in play—players from both teams gathering in a “scrimmage” or “huddle” around the ball, with a group of players trying to advance it—Harvard chose to “kick it,” or kick the ball back to a teammate. The further transformation of English rugby into American football was mainly due to the efforts of Walter Kemp, who was known as the “Father of American Football” during his lifetime.

Walter Camp

As an undergraduate and then a medical student at Yale, Kemp played football from 1876 to 1881, but — more importantly — dominated the rules committee for nearly three crucial decades, beginning in 1878. Two of Kemp’s revisions in particular effectively created the net game. The first, in 1880, improved on early Harvard innovations, eliminating scrimmage, and giving the ball to one team. He was then ejected and put into the game. (Handball became legal in 1890, although football remained an option until 1913.)

Another important rule change was necessary. Camp’s more organized way of starting the match did not require the team to give up possession of the ball. While Princeton held the ball in halves of its two matches with Yale in 1880 and 1881, both games ended in scoreless ties that bored spectators as much as it frustrated Yale players, Kemp proposed a rule that a team must advance the ball 5 yards or lose 10 on three plays, or be required to hand the ball over to the other side.

Kemp was also responsible for retaining 11 players on the team, and instituted a new scoring system in 1883 with two points for a touchdown, four points for a field goal after a touchdown, and five points for a field goal (three points for a field goal in 1909, six points for a touchdown in 1912), to create the center position, to mark the field with lines, and to propose many other innovations. Still, it was these two simple rules adopted in 1880 and 1882 that essentially created American football.

After a major rule change, the game became relatively open, with long rugby-like rounds and many lateral passes. In 1888, Kemp proposed making the tackle legal below the waist, to take advantage of the sharp back lines around the head. The new rule gave rise to team games, an offensive strategy that focused players on a defensive point, the most famous being the “Flying Wedge” game at Harvard in 1892. This style of play proved so brutal that the game was almost eliminated in the 1890s and early 1900s.

Managing violence in the game

The early spirit of football can be traced to the introduction of a rule in 1894 prohibiting the use of iron nails or plates in shoes and any metal object on a player’s person. Laws defining the boundaries between legitimate and unlawful violence have been constantly revised over the years, sometimes in response to serious concerns about deaths and injuries (for example in the 1930s as well as in the 1890s).To ensure greater safety, the number of personnel increased from two in 1873 to seven by 1983. Improvements in equipment over time also provided greater protection against serious injury.

In the 1890s, the only protection players had from blows to the head was long hair and a leather nose guard. The first headgear was in 1896 and consisted of only three leather straps. This evolved into fitted leather hats with ear lobes. The suspension helmet, which uses straps to create space between the helmet shell and the wearer’s head, was introduced in 1917. Sometimes better equipment increases the stakes of the game rather than reduces it. The plastic helmet introduced in 1939 became a lethal weapon, eventually requiring laws against “spearing”—the use of the head to initiate contact.

Expansion and reform

In 1879, the University of Michigan and Racine College in Wisconsin inaugurated football in the Midwest. Michigan under Fielding Yost in 1901-1905. and the University of Chicago under Amos Alonzo Stagg in 1905-1909. Emerge as a superpower. The game had spread to the rest of the country by the 1890s, although the Big Three—Harvard, Yale, and Princeton—continued to dominate the world of college football into the 1920s. Realizing their superiority over the later entrants, the Trio (briefly joining with the University of Pennsylvania to form the Big Four) formed the Intercollegiate Rules Committee in 1894, separate from the Intercollegiate Football Association. In the Midwest in 1895, colleges dissatisfied with this divided leadership asserted their independence by forming the Western Conference (now the Big Ten). The game also spread into the South and West, although no later conferences were formed in those regions.

Sports brutality was also widespread throughout the country. In the 1905 season, 18 young men died from football injuries. Fearing that football might be abolished altogether, President Theodore Roosevelt invited representatives (including Kemp) from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton universities to the White House in October 1905, where he urged them to reform the sport. On December 28 of that year, representatives of 62 colleges and universities (excluding the Big Three, who had refused to bend to the will of “lower” institutions for decades) met in New York to form the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, which in 1910 became the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).

To reduce team play, the group increased the yardage requirement from 5 yards to 10 for the first time at its inaugural meeting and legitimized the forward pass, the final element in the creation of American football. The formation of the NCAA effectively ended the era in which the Big Three (and Walter Kemp personally) dictated the rules of the game to the rest of the football world. It also ended student involvement in officiating the game, although the question of who should govern college football—coaches, alumni, boosters, or college administrators—would dog the NCAA throughout its history.

The persecution did not end with the amended laws of 1906. New crises led to additional rule changes in 1910 (requiring seven men) and 1912 (increasing the number of downs from 3 to 10 yards) to eliminate team play. The forward pass did not immediately change the game. The restrictions laws of 1906 made passing more dangerous than cheating, and after years of careful experimentation, the Army at Notre Dame in 1913 highlighted the great possibilities in the passing game. However, it would take another three decades – during which restrictive rules were gradually dropped and the circumference of the ball was reduced to facilitate passing – before these possibilities were fully realized.

Sport and spectacle

This early period in American football was also early in another way. Beginning in 1876, the original Association of Intercollegiate Football held a championship game on Thanksgiving Day at the end of each season, pitting the top two teams from the previous year against each other. The game was originally played in Hoboken, New Jersey, but in 1880 it was moved to New York City to facilitate the participation of students from all universities in the association in the game. The number of attendees for this first competition in New York reached 5,000 people. By 1884 the number had reached 15,000. It reached 25,000 by 1890 and 40,000 by 1893, the last Thanksgiving game played in the city. By then, game reports in New York’s major newspapers were three pages long in an eight-page spread, and news agencies were reporting to all parts of the country.

By the 1890s, the extracurricular activity at a few elite universities in the Northeast had become a spectator sport with a nationwide audience. College football is known as much for its bands, cheerleaders, pep rallies, bonfires, homecoming dances, and alumni reunions as it is for its athletic excitement. Satisfying the public’s desire for entertainment while furthering the educational mission of the institution has faced a dilemma that college administrators have grappled with for more than a century. For some in the general public, college football’s association with institutions of higher education and immersion in the collegiate spirit has lent the sport a kind of amateur purity. Others argue that colleges’ commitment to academic goals while marketing their sports teams is simply hypocritical.

College football’s golden age

The sport was temporarily suspended after World War I, and college football came into full bloom in the 1920s, when it became widely recognized as America’s greatest sporting spectacle (unlike baseball, which was the national pastime). The first soccer stadiums at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton were built on ancient Greek stadia and the Roman Colosseum, and their architecture reveals much about soccer’s cultural status. With the stadium construction boom of the 1920s, attendance doubled, exceeding 10 million by the end of the decade, and press coverage of the game expanded at a similar rate. The daily newspaper played an important role in the 1880s and 1890s, introducing football to a popular audience that had nothing to do with the universities and their teams. Commercial radio appeared in 1920 and began broadcasting football matches regularly a year later.

By the end of the decade, all three networks were broadcasting a slate of games every Saturday, and local stations were covering all home team games. By 1929, the five newscast companies devoted about one-fifth to one-quarter of their footage to football drops. General interest magazines such as Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post regularly feature articles by or about famous coaches or players, as well as short stories about the girl and the big-game-winning star. Every fall, movie theaters show an array of college football musicals and melodramas depicting kidnapped heroes who escape just in time to score the winning goal.

Red Grange and professionalism

The 1920s saw Red Grange emerge as football’s first true celebrity. Grange received national recognition for his outstanding performances in games against Michigan and Pennsylvania, but he also caused the biggest controversy in sports since the 1906 rule change when he left the University of Illinois (without graduating) to join the Chicago Bears of the National Football League. The 1920s saw Red Grange emerge as football’s first true celebrity.

Grange received national recognition for his outstanding performances in games against Michigan and Pennsylvania, but he also caused the biggest controversy in sports since the 1906 rule change when he left the University of Illinois (without graduating) to join the Chicago Bears of the professional National Football League. College football has been regularly attacked in intellectual journals, but the routine celebration of the sport in daily and weekly coverage of the popular media has obscured any criticism. A Carnegie Foundation report in 1929 documenting professionalism at 84 of the 112 institutions alarmed many college administrators but was generally dismissed by the public and sportswriters who had fueled his passion for sports.

Bowl games

In the 1920s and 1930s, colleges and universities throughout the Midwest, South, and West, along with local civic and business elites, began campaigns to gain national recognition and economic development through their football teams. They organized regional conferences—the Big Ten and Big Six (now Big 12) in the Midwest; Southern, Southeastern, and Southwestern Conferences in the South; and the Pacific Coast Conference in the West, “all-sided” games scheduled where regional prestige is at stake.

The Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California, on New Year’s Day, was first contested between Stanford and Michigan in 1902, then began annually in 1916, determined an unofficial national champion, and was also a highly profitable commercial venture. The Rose Bowl was first contested between Stanford and Michigan on New Year’s Day in Pasadena, California in 1902, became annual in 1916, determined an unofficial national champion, and was also a highly profitable commercial venture.

Knute Rockne and the influence of coaches

A hallmark of American football is the fame and prestige given to the most successful and innovative coaches. Early innovators were men like Walter Kemp (not a craftsman trainer but a mentor), Amos Alonzo Stege at the University of Chicago, George Woodruff at Pennsylvania, and Loren DeLand at Harvard, instructors who developed the V-Truck, In the 1890s, the game over, the back tackle, the back guard, the flying wedge, and other mass formations revolutionized and nearly decimated the game. The most influential of the early coaches was Pop Warner, whose backfield formations (single wing and double wing) developed at Carlisle, Pittsburgh, and Stanford. It became the dominant attacking system by the 1930s.

The only competitor to Pop Warner’s wing configurations of the 1920s and 1930s was Knute Rockne’s Notre Dame box, which modified the T-box shape from the improv first developed by Stagg. A series of rule changes eventually rendered the box change ineffective, but Rockne, football’s first celebrity coach, was not so much a master teacher and innovator as a motivator. Under his leadership, Notre Dame developed the nation’s dominant football program.

The only team of their era to follow Malik Gore and challenge his mark, they too were attacked and then forced to do so in extremely unfavorable circumstances. The 1920s were marked by anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant bigotry in much of the country, and Notre Dame’s teams were decidedly Roman Catholic and racist. College football was transformed in the 1920s and 1930s by the children of Italian, Polish, Jewish, and other immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, most of them Catholic universities (more than a dozen Midwestern universities, plus Fordham, Saint Mary’s, Notre Dame, and Penn State).

Known as the Ramblers or the Gypsies (the nickname “Fighting Irish” was adopted in the late 1920s), Notre Dame built a national schedule out of necessity rather than design. Buoyed by games from nearby Big Ten rivals, Rockin has scheduled matchups with Army, Georgia Tech, Southern California, Southern Methodist, and Nebraska — a full, crossover schedule rather than one or two key games. University administrators quickly realized the benefits, as Notre Dame became a representative school for Catholics and recent immigrants throughout the country. In the era of college building through big-time football, Notre Dame became a model that many others sought to emulate.

The birth of professional football and its early development

As college football evolved, professional football struggled for respect. The group of teams that became the National Football League (NFL) was organized in 1920 as the American Professional Football Association (renamed in 1922), with Jim Thorpe as its designated president. Former (and sometimes current) college stars had been playing for money since 1892, first for sports clubs in western Pennsylvania, then for openly professional teams formed mostly in small towns in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois. In its first season, in 1920, the APFA had 14 teams, including George Halas’s Decatur (Ill.) Staleys, who in 1922 became the Chicago Bears, the dominant team in the NFL for most of its early days. Joe Carr, an experienced promoter, succeeded Thorpe as president in 1921 and held the position until he died in 1939.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, league membership ranged from 8 to 22 teams, most of which were not in major cities but in cities such as Akron, Canton, Dayton, and Massillon, all in Ohio. Racine, Wisconsin; And Rockford, Illinois. With professionalism widely considered the biggest threat to college football, professional football was held in somewhat greater respect than professional wrestling. The Red Granges’ professionalization in 1925 gave the professional game a temporary boost, but interest in professional football could only be sustained in franchised communities.

American youth football

One of the essential aspects of football before the era of television was its local roots. In small towns, where there is no local college or professional team, community identity, and pride are often invested in the high school team. In 1920, the year the NFL’s predecessor was organized, the predecessor to the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFSHSA, later NFHS) was also formed, as high school sports were expanding across the country. Beginning in the 1930s, six-man and then eight-man versions allowed even the smallest rural schools to field field teams.

Local sentiment for high school football has varied widely, with some communities becoming known for investing in the schoolboy game that was normally reserved for the big-time college game. The December playoffs between the Catholic and public school champions in Chicago attracted 120,000 people in the 1930s, and states like Ohio and Texas became known for their passion for high school football.

Youth leagues have also been formed in most communities, some through primary schools, some through local clubs, and some affiliated with national organizations such as the Catholic Youth Organization or Pop Warner Football League. Concerns about injuries have always been an issue in youth football, but the game was widely regarded as a character builder. By the late 1930s, football was established not only as an intercollegiate, interscholastic, and professional sport but also as a part of American life.

The racial transformation of American football

By the end of World War II, very few African-American players had the opportunity to play mainstream soccer at any level. The separate and unequal world of black football first emerged in the 1890s as part of the broader expansion of college football. The first documented all-black college game was played in 1892 between Biddle University and Livingston College in North Carolina. The first black college conferences, the Colored Intercollegiate Athletic Association and the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference were formed in 1912, followed by the Southwestern Athletic Conference in 1920 and the Midwest Athletic Association in 1926.

Black college football was severely underfunded, but it had its own All-American teams (stars like “Jazz” Byrd, Ben Stevenson, “Tarzan” Kendall, and “Big Train” Moody), its major rivalries (Howard Lincoln, Tuskegee Atlanta, Morgan Hampton, see her page) and scandals. All this happened outside the awareness of the football public but was fully covered by the thriving black press.

However, mainstream football was not completely isolated. William Henry Lewis and William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson were black teammates at Amherst College in 1889, and Lewis made Walter Kemp’s All-America team in 1892 when he went to Harvard to play football while attending law school (he later became an assistant U.S. attorney).

Bowl games and the national championship

Even as bowl games became popular in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, they were overshadowed by controversy, as their sport was marketed to amateurism and the season was lengthened at the expense of academics, but resistance faded when televised contests caused financial losses and the team became a major source of conference revenue. However, a new controversy arose in the 1970s regarding the Bowles’ inability to produce an unambiguous national champion.

The perpetual call for a national championship playoff, resisted by advocates of traditional bowl games, eventually led to the creation of the Bowl Alliance in 1992_Four major bowl games (Cotton, Fiesta, Orange, Sugar), five major conferences (excluding the Big Ten and Pac-10), and independent Notre Dame – to face off against two highly ranked teams in the championship game that will alternate between the four bowls. In 1995, the Bowl Coalition was replaced by the Bowl Alliance (which included six conferences, Notre Dame, and just three bowls), but the absence of the Rose Bowl, Big Ten, and Pac-10 left the scheme deeply flawed.

In 1998, the Rose Bowl and its two participating conferences joined the Bowl Championship Series (BCS), which included all major teams and conferences, with the national championship game now taking place in the Rose, Orange, Sugar, and Fiesta Bowls. This controversy arose in 2010, and a new system was put in place for the College Football Playoff that matched the top four teams in the nation as determined by the selection committee in 2014.

The rise of the NFL

Connected to a national audience through television—and without any commitment to maintaining character or academic standards—professional football became the most exciting success story in American sports in the second half of the twentieth century. Even more so than college football, television has become the lifeblood of professional sports, with increasingly lucrative television contracts guaranteeing big profits for each club, no matter how well they perform on the field.

In the 1950s, when college officials were concerned about television, NFL Commissioner Bert Bell quickly embraced it and won congressional approval to black out television coverage in cities where local teams were playing. In one fell swoop, Bell’s efforts ensured maximum attendance for the league’s 12 clubs with little impact on the size of the league’s rapidly growing television audience.

The NFL faced competition from a new competitor in 1960, when the American Football League (AFL), sponsored by Texas billionaire Lamar Hunt, fielded teams in eight cities, three of which competed directly with NFL franchises. A television deal with NBC gave the AFL financial security that none of its predecessors had, and the NFL and AFL agreed to a merger in 1966, which was completed in 1970 with 26 clubs in two conferences. The passing-oriented NFL created more excitement for professional football as well as for the sport’s most charismatic player, New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath.

The merger also brought about the Super Bowl, which quickly became the most popular and profitable of all sporting events in the United States. Super Bowl I (not by that name yet) was played between the Green Bay Packers and Kansas City Chiefs after the 1966 season, with more than 40 percent of the nation’s television sets tuned to the two networks broadcasting the game. This percentage never fell below 36, peaking at nearly 50 in 1982, with the match eventually watched by a global audience of 130 million Americans. The Super Bowl has become a major urban ritual, as well known for the fanfare surrounding it — including the halftime show — and commercials for million-dollar football games.

Strategic developments

The game continued to innovate on the field. Lacking a “college spirit,” the NFL has always prioritized entertainment since the 1930s. The NFL formed its own rules committee in 1933 and moved the goalposts to the goal line (to facilitate field goals), liberalized the passing rules, and held the ball 10 yards from the sidelines when it went out of bounds.(Until then, the ball had been placed on the sideline, and a game had been lost for getting it closer to the middle of the field.) Later changes, in 1935 and 1972, finally placed the ball next to the goalposts (colleges made similar changes but settled on a “hash mark” one-third of the field). When new rules introduced the game, the Chicago Bears under coaches George Halas and Ralph Jones, with the assistance of University of Chicago coach Clark Shaughnessy, reintroduced the old T formation, which eventually replaced the single wing as the dominant offensive formation. Quarterback Sammy Bowe and receiver Don Hutson took the passing game to new levels, while most college teams still played a conservative, low-scoring style.

Pass defense has always been either man-to-man or zone (each fullback covers a zone). In the 1970s, when zone defenses virtually eliminated long passes, powerful running games — including linebackers like Buffalo’s O.J. Simpson, Larry Seneca, Miami’s Jim Keck, and Pittsburgh’s Franco Harris and Rocky Blair dominated the NFL.Historic rule changes in 1977 — prohibiting defensive contact with wide receivers for more than five yards and allowing offensive linemen to block with open hands — restored the advantage to passing offenses. Small, fast offensive linemen gradually disappeared, replaced by massive 300-pound (140 kg) frames that could block pass rushers with their outstretched arms and hands.

(There were eight 300-pounders in the NFL in 1986 and 179 in 1996, and the majority of linemen in the league weighed over 300 pounds in 2010.) Led by the so-called West Coast offense developed by Bill Walsh for San Francisco, the Wave never went beyond 4 games. In 1980, for the first time since 1969, the plays were passed). Other coaches developed run-and-shoot offenses, no-blocking offenses, and one-back offenses (with four wide receivers and no tight ends). Defensive coaches responded with a “combo” pass defense (a combination of zone and man-to-man), and the cornerback who could dominate a wide receiver himself emerged as the new star (Devon Sanders became the prototype for these “lockdown corners”). Running attacks increasingly featured a single linebacker, making star players such as Tony Dorsett, Eric Dickerson, Walter Payton, Barry Sanders, Emmitt Smith, and LaDayne Tomlinson.

Play a game

An American football field is 120 yards (109.8 m) long (including two 10-yard [9.1 m] end zones) and 53.33 yards (48.8 m) wide. A coin toss at the start of the game determines who will kick the ball at the 30, 35, or 40-yard line (at the intercollegiate, professional, and academic levels, respectively) and which goal each team will defend. After a kickoff, the team’s center in possession of the ball puts it in play by passing it between his legs to the quarterback, who hands it off to another linebacker, passes it to the receiver, or runs it himself.

Opponents attempt to stop any progress toward their goal line by tackling, hitting the runner, or intercepting passes. The offensive team gains a “first down” by advancing the ball 10 yards four or fewer times and can hold the ball with repeat first downs until a score is scored or the defense gains possession or intercepts the pass. Failing to get a first down, the offensive side must hand the ball over, usually by kicking it on fourth down. An offense is scored by advancing the ball across the opponent’s goal line (six-point field goal) or by placing it over the crossbar and between the goal posts (three-point field goal).

After a touchdown, the ball is placed on the three-yard line, and the scoring team is allowed to attempt a conversion: a place kick across the goalposts for one point or a running pass or completion across the goal line for two points. (In the NFL, the ball is placed on the 15-yard line for a punt attempt and on the 2-yard line for a two-point conversion attempt.)The defense can score by tackling the ball carrier across the other team’s goal line for a touchdown (to secure two points), or by replaying a failed conversion attempt to the opponent’s goal line (two points).

Another kickoff, by the scoring team, follows each score, and the same pattern is repeated until the playing time for half is over (30 minutes for intercollegiate and professional soccer, 24 minutes for academic). The second half is followed by a 15 or 20-minute intermission, during which teams choose to bat or toss after losing the initial coin toss. The team with the most points by the end of the game is the winner, and tied games are decided by overtime play, which is determined by different rules at different levels.

The game is overseen by seven NFL officials, four to seven college officials, and at least three high school officials. All refereeing staff has a referee with overall supervision and control of the match, assisted by the referees, assistant referees, field judges, back judges, line judges, and side judges. The referees are the sole referrer of the result, and their decisions on the rules of the game and other matters are final. The referee declares the ball ready for play and monitors the time between plays when it has not been assigned to another referee. The referee also administers all penalty kicks.